Hurricane Mitch

Mitch at peak intensity just to the northeast of Honduras on 26 October | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 22 October 1998 |

| Extratropical | 5 November 1998 |

| Dissipated | 9 November 1998 |

| Category 5 major hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 180 mph (285 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 905 mbar (hPa); 26.72 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | >11,374 (Second-deadliest Atlantic hurricane on record) |

| Damage | $6.08 billion (1998 USD) |

| Areas affected | Central America (especially Honduras and Nicaragua), Yucatán Peninsula, South Florida, Jamaica, British Isles |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1998 Atlantic hurricane season | |

| History

Effects Other wikis | |

Hurricane Mitch was an extremely deadly and catastrophic Atlantic hurricane, which became the second-deadliest tropical cyclone in the Atlantic basin on record. Mitch caused 11,374 fatalities in Central America in 1998, including approximately 7,000 in Honduras and 3,800 in Nicaragua due to cataclysmic flooding from the slow motion of the storm. It was the deadliest hurricane in Central American history, surpassing Hurricane Fifi–Orlene, which killed slightly fewer people in the same area in 1974. Mitch was the deadliest Atlantic hurricane in the satellite era, and the second-deadliest on record in the Atlantic, only behind the Great Hurricane of 1780 which killed at least 22,000 people.

The thirteenth named storm, ninth hurricane, and third major hurricane of the 1998 Atlantic hurricane season, Mitch formed in the western Caribbean Sea on 22 October, and after responding to extremely favorable conditions, it rapidly strengthened to peak at Category 5 status, the highest possible rating on the Saffir–Simpson scale. After drifting southwestward and weakening, the hurricane hit Honduras as a minimal Category 1 hurricane. Mitch roved through Central America, regenerated in the Bay of Campeche, and ultimately impacted Florida as a strong tropical storm. It then became extratropical and accelerated northeastward across the North Atlantic, before dissipating on 9 November. At the time, Mitch was the strongest Atlantic hurricane observed in the month of October, surpassing Hurricane Hattie of the 1961 season. The record would stand for seven years until it would be broken by Hurricane Wilma of the 2005 season. In addition, Mitch is the ninth-most intense Atlantic hurricane on record, tied with Hurricane Dean in 2007 in terms of pressure.

Being "the deadliest Atlantic hurricane" in over 200 years,[1] Mitch caused catastrophic impacts across its path, but the most disastrous impacts came from Honduras, which suffered over half of the total deaths. The president of Honduras, Carlos Roberto Flores, estimated that Mitch set back about 50 years of economic development. The storm wrecked about 35,000 houses and damaged another 50,000, leaving up to 1.5 million people homeless, about 20 percent of the country's population. Mitch directly caused $2.005 billion in damage,[nb 1] with an additional $1.8 billion in indirect costs. Most of the damage were ruined crops, and cash crop exports were cut by 9.4 percent in 1999, largely due to the storm. Over 70 percent of the transportation infrastructure was damaged, mostly damaged highways and bridges. Widespread areas experienced power outages, and about 70 percent of the country lost its water sources after the storm. In Tegucigalpa, a large landslide affected three neighborhoods and formed a temporary dam. Throughout the country, there were at least 7,000 fatalities, some reported in each department. Following the storm, officials in Honduras requested international assistance, which totaled $2.8 billion over a several-year period. Despite this, the gross domestic product began decreasing at the end of 1998, and contracted by 1.9 percent in 1999. Officials enacted a widespread curfew following the storm, and for 15 days temporarily restricted constitutional rights to maintain order. There were outbreaks of various diseases, and many residents faced food and water shortages.

Due to the slow motion from 29 October to 3 November, Hurricane Mitch dropped historic amounts of rainfall in Honduras, Guatemala, and Nicaragua, with unofficial reports of up to 75 inches (1,900 mm). Deaths due to catastrophic flooding made it the second deadliest Atlantic hurricane in history after the Great Hurricane of 1780; at least 11,374 people were confirmed to have been killed with over 11,000 left missing by the end of 1998; the true death toll is unknown. Additionally, roughly 2.7 million were left homeless as a result of the hurricane. Total damages caused by the hurricane were estimated to be around $6 billion (1998 USD). The name "Mitch" was retired, and will not be used for another Atlantic tropical cyclone.[2]

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Pressure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hPa | inHg | |||

| 1 | Wilma | 2005 | 882 | 26.05 |

| 2 | Gilbert | 1988 | 888 | 26.23 |

| 3 | "Labor Day" | 1935 | 892 | 26.34 |

| 4 | Rita | 2005 | 895 | 26.43 |

| Milton | 2024 | |||

| 6 | Allen | 1980 | 899 | 26.55 |

| 7 | Camille | 1969 | 900 | 26.58 |

| 8 | Katrina | 2005 | 902 | 26.64 |

| 9 | Mitch | 1998 | 905 | 26.73 |

| Dean | 2007 | |||

| Source: HURDAT[3] | ||||

Tropical Depression Thirteen formed on October 22 over the southwestern Caribbean Sea, from a tropical wave that exited Africa on October 10. It executed a small loop, and while doing so intensified into Tropical Storm Mitch. A weakness in a ridge allowed the storm to track slowly to the north. After becoming disorganized due to wind shear from an upper-level low, Mitch quickly intensified in response to extremely favorable conditions,[4] including warm waters and good outflow.[5][6] It became a hurricane on October 24 and developed an eye.[7] After turning to the west, Mitch rapidly intensified, first into a major hurricane on October 25 and then into a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale the next day.[4]

At peak intensity, Mitch maintained maximum sustained winds of 180 mph (290 km/h) while off the northern coast of Honduras. Hurricane Hunters reported a minimum barometric pressure of 905 mbar (26.7 inHg), which at the time was the lowest in the month of October and tied for the fourth lowest for any Atlantic hurricane. Initially, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) and various tropical cyclone forecast models anticipated a turn to the north, threatening the Yucatán Peninsula. Instead, Mitch turned to the south, due to a ridge that was not observed while the storm was active.[4] Land interaction imparted weakening,[8] and the hurricane made landfall on Honduras on October 29 with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h).[4]

While over land, Mitch moved slowly westward through Central America, while continuing to produce deep convection over waters.[9] The surface circulation dissipated on November 1. The next day, the remnants of Mitch reached the Bay of Campeche. On November 3, the remnants redeveloped into a tropical storm just off the coast of the Mexican state of Campeche, and a day later the storm made another landfall just north of the city of Campeche. Mitch accelerated to the northeast ahead of a cold front, moving across the Yucatán peninsula and re-entering the Gulf of Mexico. The storm retained winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) before it made a final landfall near Naples, Florida on November 5. Shortly after crossing the state, Mitch transitioned into an extratropical cyclone. The NHC tracked this storm until November 9, when former Hurricane Mitch passed north of Scotland.[4]

Preparations

Various tropical cyclone watches and warnings were issued due to the hurricane.[4] The NHC recommended early on October 26 for a hurricane warning to be issued for the northeastern Honduran coast, although difficulties in communications prevented their immediate implementation.[10] Within a few hours, a hurricane warning was in place between Limón to the Honduras and Nicaragua border, including the offshore Swan Island.[11] When Mitch still failed to turn to the north, the government of Honduras issued a hurricane warning for the remainder of their coastline.[12] Due to the threat, the government of Honduras evacuated some of the 45,000 citizens on the Bay Islands and prepared all air and naval resources.[13] On October 26, the Honduran Permanent Contingency Commission coordinated with neighboring countries regarding the storm. Officials initially issued a state of emergency for the offshore islands and five coastal departments, which was later extended to the rest of the country. The government increased emergency spending and created a National Emergency Commission. Officials advised residents to evacuate in flood-prone areas, although many people stayed for fear of being looted. Some left to stay with relatives during the hurricane. Prisoners in Tegucigalpa Central Penitentiary were evacuated to the national stadium.[14] Before the storm struck, Honduras was facing decreased food supplies due to ongoing El Niño conditions. The economy had been growing at a rate similar to the previous year until Mitch struck,[15] and was largely dependent on exports. About 73% of the population was living in poverty when the storm struck.[16] Hurricane Mitch set back the economies of various countries in the region, including Honduras, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and El Salvador, after they had improved throughout the 1990s.[14]

The government of Belize issued a purple alert and asked for citizens on offshore islands to leave for the mainland.[13] Because the hurricane threatened to strike near Belize City as a Category 4 hurricane, much of the city was evacuated in fear of a repeat of Hurricane Hattie 37 years earlier.[17] Guatemala issued a purple alert as well, recommending boats to stay in port, telling people to prepare or seek shelter, and warning of potential overflowing rivers.[13] By the time hurricane Mitch made landfall, numerous people were evacuated along the western Caribbean coastline, including 100,000 in Honduras, 10,000 in Guatemala, and 20,000 in the Mexican state of Quintana Roo.[18]

Impact

| Region | Deaths | Ref | Damages | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belize | 11 | [17] | $50,000 | [19] |

| Costa Rica | 7 | [17] | $92 million | [20] |

| El Salvador | 240 | [21] | $400 million | [21] |

| Guatemala | 268 | [22] | $748 million | [22] |

| Honduras | 7,000 | [19][23] | $3.8 billion | [19][24] |

| Jamaica | 3 | [17] | Unknown | |

| Mexico | 9 | [17][19] | $1 million | [19] |

| Nicaragua | 3,800 | [17] | $1 billion | [17] |

| Panama | 3 | [17][19] | $50,000 | [19] |

| United States | 2 | [4] | $40 million | [4] |

| Offshore | 31 | [17] | ||

| Total | 11,374 | $6.08 billion | ||

Central America

Hurricane Mitch was the deadliest Atlantic hurricane since the Great Hurricane of 1780, displacing the Galveston Hurricane of 1900 as the second-deadliest on record. Nearly 11,000 people were confirmed dead, and almost as many reported missing. Deaths were mostly from flooding and mudslides in Central America, where the slow-moving hurricane and then tropical storm dropped nearly 36 inches (900 mm) of rain. The flooding and mudslides damaged or destroyed tens of thousands of homes, with total damage amounting to over $5 billion (1998 USD, $6 billion 2006 USD), most of which was in Honduras and Nicaragua. Prior to Mitch, the deadliest hurricane in Central America was Hurricane Fifi in 1974, which killed an estimated 8,000–10,000.[4]

Honduras

Beginning on October 26, the hurricane drew moisture from the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea to produce torrential rainfall across Honduras, producing high amounts of rainfall of over 300 mm (12 in) per day.[17][14] In some areas, high mountain peaks contributed to high precipitation totals,[4] and the highest amounts occurred in southern Honduras.[25] The highest official total was 928 mm (36.5 in) at Choluteca, which represented more than half of the annual precipitation average; at the same location, 466.7 mm (18.37 in) fell in a 24-hour period on October 31, which was more than double the previous record set in 1985.[14] At Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras in the capital Tegucigalpa, rainfall totaled 294 mm (11.58 in).[4] The total of 120.4 mm (4.74 in) on October 30 broke the record set in 1966 for the wettest day. At La Ceiba near where the storm made landfall, Mitch produced 874 mm (34.4 in) of rainfall, which is 30% of its annual rainfall; of the total, 284.1 mm (11.19 in) fell on October 27, which was the third highest amount there on record.[14] There were unofficial rainfall totals in Central America as high as 1900 mm (75 in); rain gauges in mountainous areas were washed away.[17] The high rainfall caused many rivers in the country to overflow "to an unprecedented extent this century", as described by the United Nations.[14] The greatest depth recorded was 12.5 m (41 ft) on the Ulúa River near Chinda, whilst the greatest width recorded was 359 m (1,178 ft) on the Río Lean near Arizona. The rainfall also caused widespread mudslides across the mountainous country.[26] The flooding caused the Choluteca River to change its course, forming an avulsion. Widespread flooding near the northern coast left behind about 1 m (3.3 ft) of sediment, which ruined forests and shrimp ponds. Flooding also affected the Pacific coast along the Gulf of Fonseca, leaving behind debris and sediment.[27] In the country's interior, particularly the southern portion, the high rainfall caused hundreds of landslides, many of them shallow and about 95% in the form of debris flow. However, two earthflows caused significant damage near Tegucigalpa.[25]

While offshore northern Honduras, Hurricane Mitch passed over Guanaja island.[4] Two days of winds exceeding 200 km/h (125 mph) destroyed nearly all of the plants and trees on Guanaja, uprooting or knocking down almost the entire mangrove forest.[27] It is estimated that the hurricane produced waves of 44 ft (13 m) in height.[28] High waves eroded northern coastlines and damaged lagoons.[16] Most of the Bay Islands had damage to their water facilities.[15]

Overall, Hurricane Mitch killed about 7,000 people in Honduras,[14] with 11,000 missing in the months after the storm.[17] There were 8,000 people listed as missing about ten days after Mitch struck, although problems with record-keeping made it difficult to determine the exact total. Choluteca Department in the southern portion of the country had the most deaths, with 1,200 fatalities. Francisco Morazán Department, which includes Tegucigalpa, had about 1,000 deaths, and Yoro Department had 911 fatalities. There were deaths in every department, however.[14] Many of the dead were buried in mass graves or were cremated.[17] The storm injured 12,272 people nationwide,[15] mostly in Choluteca and Cortés departments.[14] Throughout the country, damage was estimated at L52,345,000,000 ($3.8 billion).[15] Of this, $2.005 billion was from direct damages and the remainder from indirect costs. The overall impact represented about 70% of Honduras's annual gross domestic product (GDP).[16] The hurricane affected nearly the entire population and causing damage in all 18 departments.[14] The United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean estimated that Mitch caused the worst floods of the 20th century in the country.[16] Honduras's Social Fund for Housing estimated that 35,000 houses nationwide were destroyed with another 50,000 damaged,[15] many of which were poorly built or in flood-prone areas.[16] This left up to 1.5 million people homeless – about 20% of the total population[17] – and was the highest number of victims from any natural disaster in Honduras's history. Over 30% of the populations of Choluteca, Colón, and Cortés departments were left homeless.[14] Housing costs were estimated at $344 million, including $221 million in housing damage; the rest included the costs for shelters, removal of debris, and loss of rent.[16]

Across Honduras, agriculture sustained serious damage, with initial estimates of 70% of crops destroyed.[17] Flooding affected about 29% of the country's arable land, much of covered for an extended period of time.[15] This washed away large areas of topsoil, which would take a long period of time to recover.[16] About 85% of the banana crop was lost, along with the loss of 60% of melons,[15] 60% of sugar cane,[16] and 58% of corn.[15] About one-third of the corn crop had already been harvested.[16] About 50,000 bovine were killed, as were 60% of the fowl population.[15] Crop and agricultural damage totaled about $1 billion,[16] which would take the country years to recover.[17] Poor road conditions following the storm prevented crops from being dried, which caused further damage.[16] Mitch caused substantial damage to the nation's agricultural industry, particularly in areas inhabited by mestizos and indigenous groups. Bananas, plantains, and manioc, all of which are historically important export crops for Honduras, were all essentially destroyed, as were about 80% of rice farms.[29]

An estimated 70–80% of the transportation network was destroyed, including most bridges and secondary roads,[17] amounting to $236 million in damage. In mountainous areas, floods carrying debris damaged roads and bridges. A total of 9,198 m (30,177 ft) of bridges were damaged or destroyed, and an additional 2,045 m (6,709 ft) of approach roads were likewise damaged. Several vehicles were washed away due to the floods. In contrast to roads, there was little railway damage. There was minor impact to the nation's airports, limited to some damage to air traffic equipment. Seaports also sustained minor damage, although many lost electronic equipment. Hurricane Mitch left widespread power outages after damaging more than 385 km (239 mi) of power lines and several power plants. About 11% of Honduras's telephone lines were damaged during the storm.[16] Landslides and flooding contaminated aqueducts in several cities, including 1,600 systems in rural areas.[15] Many cities sustained damage to their water network,[16] and about 70% of Honduras lost access to fresh water after the storm, although many rural areas had already been experiencing water shortages.[14] The combined damage to transportation, communication, utilities, including power and water, was estimated at $665 million.[15] Communications were disrupted after power outages, and there were also fuel and water shortages.[17] Flooding damaged or destroyed industrial areas of Honduras, which affected exports and domestic products.[15] Six maquiladora factories were damaged in the northern portion of the country, and one was destroyed in La Ceiba.[16] Many businesses shut down, leaving many people unemployed who already lost their homes.[14] Mitch also destroyed 123 health facilities nationwide and wrecked 4,835, or 23%, of the nation's classrooms.[15] As a result, most classes that would have gone until November 30 were ended about a month early, allowing teachers to assist in helping others.[14]

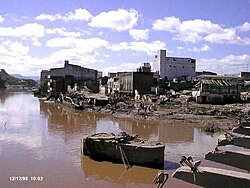

Severe flooding occurred in the northern region,[14] which washed away more than 25 entire villages.[17] In San Pedro Sula in northwestern Honduras, flooding covered several neighborhoods and the international airport.[14] Near the coast, high waves destroyed hotels and houses while swollen rivers flooded nearby areas. Damage was heaviest in Colón and Atlántida departments.[15] In the latter department, the Cangrejal River left heavy damage along its path after it flooded. In Choluteca and Valle departments in the southern portion of the country, river flooding swept away houses and affected neighborhoods.[16] High water levels along the Choluteca River affected the capital, Tegucigalpa,[15] reaching levels 10 m (33 ft) above their banks.[14] Mitch largely destroyed the center of the city, including many residential buildings along river banks.[16] The floods damaged about one-third of buildings, including some more than 350 years old.[17] The storm destroyed the primary water mains in Tegucigalpa and neighboring Comayagüela, and 23 km (14 mi) of water piping had to be repaired.[16] In central Tegucigalpa, there was a large earthflow along Cerro El Berrinche mountain that weighed 6,000,000 m3 (210,000,000 cu ft). This landslide, the largest generated by Mitch in the country, destroyed the Colonia Soto section and damaged portions of two other neighborhoods.[25] It carried debris, trees, and rocks, forming a temporary dam along the Choluteca River laden with sewage.[14][25] Because the landslide was slow-moving, officials were able to evacuate before the river was stopped due to the temporary dam. Another smaller landslide destroyed several houses in the Colonia El Reparto section of the capital, although it was also slow-moving, and the residents were able to evacuate. Other landslides destroyed over 20 houses along the rivers in the city due to erosion along river banks.[25]

On October 27, the S/V Fantome, a schooner, last reported its location to the south of Guanaja, while trying to escape the brunt of the storm. The United States Coast Guard searched until November 4, when they observed the debris from the ship. All 31 people on board were presumed killed.[17] On the offshore Guanaja island, waters rose about 2 m (6.6 ft) during the storm.[16] The combination of storm surge and high winds severely damaged offshore islands.[17] High waves eroded northern coastlines and damaged lagoons.[16] Most of the Bay Islands had damage to their water facilities.[15] Two days of winds exceeding 200 km/h (120 mph) destroyed nearly all of the plants and trees on Guanaja, uprooting or knocking down almost the entire mangrove forest.[27] Most mangrove trees were an average of 11.2 m (37 ft) in height before they fell. Those remaining standing were damaged internally and unable to regrow. All trees lost their leaves on the island,[30] and 70% of conifer trees were knocked down.[25] Montane trees likewise experienced severe damage, although they made a recovery within a year.[30] However, no mangrove trees had regrown there by three years after the storm struck, indicating the level of destruction. Tree damage also occurred on nearby Roatán island, although to a much lesser degree,[27] and occurring on the eastern end. Winds there were generally less than 185 km/h (115 mph), and the tree damage was more random.[30]

Nicaragua

Though Mitch never entered Nicaragua, its large circulation caused extensive rainfall, with estimates of over 50 inches (1,300 mm).[17] In some places, as much as 25 inches (630 mm) of rain fell on coastal areas.[31] The flank of the Casita Volcano failed and turned into a lahar from excessive rain. The resulting mudslide ultimately covered an area 10 miles (16 km) long and 5 miles (8.0 km) wide.[17]

Two million people in Nicaragua were directly affected by the hurricane.[17] Across the country, Mitch's heavy rains damaged 17,600 houses and destroyed 23,900, displacing 368,300 of the population.[32] 340 schools and 90 health centers were severely damaged or destroyed. Sewage systems and the electricity subsector were severely damaged, and, combined with property, damage totaled to $300 million (1998 USD).[33]

Transportation was greatly affected by the hurricane, as well. The rainfall left 70% of the roads unusable or destroyed and greatly damaged 92 bridges.[34] Over 1,700 miles (2,700 km) of highways or access roads needed replacement subsequent to the storm, especially in the northern part of the country and along portions of the Pan-American Highway. Total transportation damage amounted to $300 million (1998 USD). Agricultural losses were significant, including the deaths of 50,000 animals, mostly bovines. Crops and fisheries were affected greatly as well, and, combined with agricultural losses, damage totaled to $185 million (1998 USD).[33]

The situation was further compounded by a total of 75,000 live land mines—left over from the Contra insurgency of the 1980s—that were calculated to have been uprooted and relocated by the floodwaters.[35]

In all, Hurricane Mitch caused at least 3,800 fatalities in Nicaragua, of which more than 2,000 were killed in the towns of El Provenir and Rolando Rodriguez from the landslide at the Casita volcano. The mudslide buried at least four villages completely in several feet of mud. Throughout the entire country, the hurricane left between 500,000 and 800,000 homeless. In all, damage in Nicaragua is estimated at $1 billion (1998 USD).[17]

Rest of Central America

| Deadliest Atlantic hurricanes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Fatalities |

| 1 | ? "Great Hurricane" | 1780 | 22,000–27,501 |

| 2 | 5 Mitch | 1998 | 11,374+ |

| 3 | 2 Fifi | 1974 | 8,210–10,000 |

| 4 | 4 "Galveston" | 1900 | 8,000–12,000 |

| 5 | 4 Flora | 1963 | 7,193 |

| 6 | ? "Pointe-à-Pitre" | 1776 | 6,000+ |

| 7 | 5 "Okeechobee" | 1928 | 4,112+ |

| 8 | ? "Newfoundland" | 1775 | 4,000–4,163 |

| 9 | 3 "Monterrey" | 1909 | 4,000 |

| 10 | 4 "San Ciriaco" | 1899 | 3,855 |

Due to Mitch's large circulation, it dropped heavy precipitation as far south as Panama and Colombia, especially in the Darién and Chiriquí provinces. The flooding washed away a few roads and bridges, and damaged numerous houses and schools, leaving thousands homeless.[36] The hurricane left three casualties in Panama.[17]

In Costa Rica, Mitch dropped heavy rains, causing flash flooding and mudslides across the country, mostly in the northeastern part of the country.[17] The storm impacted 2,135 homes to some degree, of which 241 were destroyed,[20] leaving 4,000 homeless.[31] Throughout the country, the rainfall and mudslides affected 126 bridges and 800 miles (1,300 km) or roads, mostly on the Inter-American Highway which was affected by Hurricane Cesar, two years prior. Mitch affected 115 sq mi (300 km2) of crop lands, causing damage to both export and domestic crops. In all, Hurricane Mitch caused $92 million in damage (1998 USD)[20] and seven deaths.[17]

While drifting through El Salvador, the hurricane dropped immense amounts of precipitation, resulting in flash flooding and mudslides through the country. Multiple rivers, including the Río Grande de San Miguel and the Lempa River overflowed, contributing to overall damage. The flooding damaged more than 10,000 houses, leaving around 84,000 homeless[21] and forcing 500,000 to evacuate.[37] Crop damage was severe, with serious flooding occurring on 386 sq mi (1,000 km2) of pasture or crop land. The flooding destroyed 37% of the bean production, 19% of the corn production, and 20% losses in sugar canes. There were heavy losses in livestock as well, including the deaths of 10,000 cattle. Total agricultural and livestock damaged amounted to $154 million (1998 USD). In addition, the flooding destroyed two bridges and damaged 1,200 mi (1,900 km) of unpaved roads. In all, Mitch caused nearly $400 million in damage (1998 USD) and 240 deaths.[21]

Similar to the rest of Central America, Mitch's heavy rains caused mudslides and severe flooding over Guatemala. The flooding destroyed 6,000 houses and damaged 20,000 others, displacing over 730,000 and forcing over 100,000 to evacuate. In addition, the flooding destroyed 27 schools and damaged 286 others, 175 severely. Flooding caused major damage to crops, while landslides destroyed crop land across the country. The most severely affected crops for domestic consumption were tomatoes, bananas, corn, other vegetables, and beans, with damaged totaling to $48 million (1998 USD). Export crops such as bananas or coffee were greatly damaged as well, with damage amounting to $325 million (1998 USD). Damage to plantations and soil totaled to $121 million (1998 USD). The flooding also caused severe damage to the transportation infrastructure, including the loss of 37 bridges. Across the country, flooding damaged or destroyed 840 miles (1,350 km) of roads, of which nearly 400 miles (640 km) were sections of major highways. In all, Hurricane Mitch caused $748 million (1998 USD) and 268 deaths in Guatemala.[22] In addition, Mitch caused 11 indirect deaths when a plane crashed during the storm.[37]

In Belize, the hurricane was less severe than initially predicted, though Mitch still caused heavy rainfall across the country.[37] Numerous rivers exceeded their crests, though the rainfall was beneficial to trees in mountainous areas.[38] The flooding caused extensive crop damage and destroyed many roads. Throughout the country, eleven people died because of the hurricane.[37]

In Mexico, Mitch produced gusty winds and heavy rains on the Yucatán Peninsula, with Cancún on the Quintana Roo coast being the worst hit.[37] Nine people were killed from the flooding, though damage was relatively minimal.[17] The maximum 24-hour rainfall total from Mitch was 13.4 inches (340 mm) in Campeche,[39] while the highest rainfall total was 16.85 inches (428.0 mm) in Ciudad del Carmen.[40]

Caribbean Sea

Mitch was also responsible for the loss with all hands of Windjammer Barefoot Cruises' schooner Fantome. The story was recorded in the book The Ship and The Storm by Jim Carrier. The schooner, which was sailing near the center of the hurricane, experienced over 50 feet (15 m) waves and over 100 mph (160 km/h) winds, causing her to sink off the coast of Honduras.[41]

On the south coast of Cuba, the hurricane caused waves of up to 13 feet (4.0 m) high and winds gusts peaking at 42 mph (68 km/h), causing numerous tourists and workers on the Isle of Youth and Cayo Largo del Sur to leave for safer grounds.[42]

In Jamaica, where officials declared hurricane warnings 12 hours prior to its closest approach,[4] Mitch caused moderate rainfall and gusty winds for days. Strong waves hit western Jamaica, with wave heights unofficially estimated at nearly 7 feet (2.1 m) in height. The rainfall in outer rainbands, at times severe, flooded many roads across the island and left them covered with debris. One house in Spanish Town collapsed from the flooding, leaving four homeless. Many other homes and buildings were flooded, forcing many to evacuate. A river in northeastern Jamaica overflowed its banks, while heavy rainfall across the mountainous parts of the country caused numerous mudslides.[43] In all, Mitch killed three people on Jamaica.[17]

On the Cayman Islands, the hurricane caused strong waves, gusty winds, and heavy rainfall at times. Damage was relatively minimal, amounting to blown out windows and beach erosion. Strong waves damaged or destroyed many docks on the south shore of the islands, and also sank one dive ship near Grand Cayman. In addition, numerous incoming and outgoing flights were cancelled.[44]

Florida and Europe

Then a tropical storm, Mitch caused a storm surge of up to 4 feet (1.2 m) in the lower Florida Keys before making landfall on the Florida west coast. Key West International Airport reported peak wind gusts of 55 mph (89 km/h) and sustained winds of 40 mph (64 km/h), the only report of tropical storm force in the state.[4] Offshore, the Fowey Rocks Light reported wind gusts of 73 mph (117 km/h).[45] In addition, Mitch caused moderate rainfall, peaking at 7 inches (200 mm) in Jupiter, though some estimates indicate localized totals of up to 10 inches (250 mm). The storm spawned five tornadoes over the state, the strongest of which was rated F2.[4]

In the Florida Keys, multiple buildings that had been damaged by Hurricane Georges were leveled by Mitch.[17] Tornadoes from the storm damaged or destroyed 645 houses across the state, in addition to injuring 65 people.[4] Gusty winds left 100,000 without power during the storm's passage.[17] In all, Mitch caused $40 million in damage (1998 USD) in Florida and two deaths from drowning when two boats capsized.[4]

As an extratropical cyclone, Mitch passed west of Ireland and the United Kingdom. In Ireland, the storm produced gusts as high as 90 mph (140 km/h) and 30 ft (9.1 m) waves. The winds knocked down trees and power lines, leaving over 30,000 homes without power. One tree fell onto a car in Louth, severely injuring the driver. In Dublin, high winds knocked the roof off of a building, and several other buildings nationwide were damaged. The storm caused airports to close and ferry service to be suspended.[46]

Aftermath

As a result of the extreme damage and loss of life caused by Hurricane Mitch, the name Mitch was retired by the World Meteorological Organization following this storm, and will never again be used for a North Atlantic tropical cyclone. It was replaced with Matthew for the 2004 season.[47]

After the disaster, countries around the world donated significant aid, totaling $6.3 billion (1998 USD). Throughout Central America, which was recovering from an economic crisis that occurred in 1996, many wished to continue the growth of the infrastructure and economy. In addition, after witnessing the vulnerability to hurricanes, the affected governments endeavored to prevent such a disaster from occurring again.[48]

Hundreds of thousands of people lost their homes, but many took this as an opportunity to rebuild stronger houses. With a new, structurally improved foundation, homes were redesigned to be able to withstand another hurricane. However, lack of arable crop land took away the jobs from many, decreasing an already low income even lower.[49] In Costa Rica, reconstruction after the hurricane increased the number of jobs by 5.9%, lowering the unemployment rate slightly.[20]

Following the passage of Mitch, disease outbreaks occurred throughout Central America, including cholera, leptospirosis, and dengue fever. Over 2,328 cases of cholera were reported, killing 34 people. Guatemala was most affected by the bacterium, where most of the deaths occurred from contaminated food. 450 cases of leptospirosis were reported in Nicaragua, killing seven people. There were over 1,357 cases of dengue reported, though no deaths were reported from the disease.[50]

While stalling over the western Caribbean Sea, Mitch's strong winds produced strong waves, damaging local coral reefs. Later, the storm's immense rainfall led to runoff polluted with debris and fresh water. This resulted in diseases occurring within the coral. However, the hurricane's upwelling cooled the warm water temperatures, preventing significant bleaching and destruction of the coral reef.[51]

Honduras

Then-president Carlos Roberto Flores estimated that Mitch reversed 50 years of progress in the country. Officials estimated it would take at least 15 years to rebuild completely.[17] The national gross domestic product (GDP) only grew at a rate of 3% due to the storm, compared with 5.1% in 1997, due to damaged infrastructure and lingering effects.[15] In 1999, the economy of Honduras contracted by 1.9%, largely due to the storm.[52] The Honduran government increased spending by 24.7%,.[53] much of it emergency funds to restore communications and provide relief, which caused economic deficits.[15] This caused inflation to increase from 13.6% to 15.7%.[53] The Honduran government adjusted its economic plan, including privatization of various federal entities.[52] For two years, the government temporarily halted taxes to businesses affected by the hurricane.[54]

In the storm's immediate aftermath, officials enacted a widespread curfew after reports of looting and vandalism. The government temporarily restricted constitutional rights for 15 days. Officials urged residents to restrict water and fuel use, and alcohol sales were halted.[14] The widespread flooding and the crippled infrastructure forced officials to rely on a limited number of helicopters to operate search and rescue missions and deliver supplies. A helicopter carrying four people, including Tegucigalpa mayor and potential presidential candidate César Castellanos, crashed on November 1 while touring flood damage, killing everyone aboard. In some areas, residents did not receive assistance until November 12, more than two weeks after Mitch's landfall.[17] About 285,000 people remained in 1,375 shelters, many of them schools, by three weeks after the hurricane struck. Some sports stadiums and churches were also used as makeshift shelters. Overcrowding at shelters caused various diseases.[14]

Due to the hurricane and the widespread destruction, the hurricane caused outbreaks of malaria, dengue, cholera, and various fever and respiratory illnesses.[17] Ongoing flooding caused an outbreak of Leptospirosis, notably in Cortés Department.[55] There were widespread food and water shortages, leaving villagers near-starvation.[17] Damaged crops also prevented the export of cash crops,[16] and exports decreased by 9.4% in 1999.[52] Many of the people left homeless also became unemployed, and there were reductions in exports and economic growth. Officials set up shelters that housed 285,000 people for about a month.[15] In Tegucigalpa, where the Choluteca River was dammed by a landslide, a temporary lagoon filled with sewage persisted for about two months, until a crew from the United States Army Corps of Engineers and United States Geological Survey dug a channel to drain the water.[25]

Even before the storm struck, the government of Honduras issued an appeal for international assistance. In the immediate aftermath, the United States provided $875,000 in aid. A portion went to purchasing and delivering food, while the majority used airplanes to participate in rescue missions and deliver supplies, such as plastic sheets and water. The United States ultimately gave $15 million in aid to Honduras through various United Nations organizations. Mexico donated food, medicine, and clothing, and Cuba sent a team of doctors and mobile hospitals. Uruguay donated a pump for the city of Choluteca to restore water there. Several European Countries sent aid to Honduras, in addition to donations from the European Union. France sent medical equipment, and the government of Japan provided a field hospital that helped 300 patients per day in the center of Tegucigalpa. Following the storm, the United Nations Development Programme sent a team to Honduras and El Salvador to determine the needs of the population. The Honduran government requested the team to assess the socio-economic impact of the storm. The World Food Programme provided $17 million worth of food to the country. The Pan American Health Organization focused on restoring water systems by providing latrines, while UNICEF sent large water tanks.[14]

The Inter-American Development Bank approved $197.4 million in loans in 1998, most of which due to Hurricane Mitch. The loans were to assist in rebuilding damaged infrastructure, including for water systems, transportation, and houses.[15] Various countries provided nearly $2.8 billion to the country in aid,[52] which limited the annual debt following the hurricane's damage.[53] The foreign aid due to the storm largely ended by 2003.[56] Overall cost for reconstruction was estimated at $2.5 billion, which was estimated to take four years. The cost for repairing the damaged houses was estimated at $484.8 million. Following the storm, workers made emergency repairs to the destroyed bridges and roads. The cost for rebuilding roads was higher than their damage cost due to planning for future flooding. Within a month, there were repairs to the power grid to a level of 550 MW, or 91.7% of what it was before Mitch struck. Water companies restored water to 60% of Tegucigalpa within a month of the storm striking.[16]

Millions of Hondurans were left homeless as a result of Mitch, and the most substantial reconstruction efforts took place in Honduras and neighboring Nicaragua.[57] Hundreds of refugee centers each holding thousands of displaced Hondurans were set up in cities. However, many of these centers were ineffective at providing food and resources. Part of this was due to confusion between the government, churches, and local commerce groups over how supplies were to be allocated and distributed. There were significant resources intended for refugees, but authorities often hoarded it in heavily-guarded warehouses. The entire hurricane and subsequent refugee crisis did bring to light the problems Hondurans faced relating to contagious diseases, and the country received considerable medical attention in the aftermath of Mitch.[58]

Outside of cities, the recovery took longer, with rural areas receiving little areas compared to urban areas.[59] The destruction of crops also led to malnourishment and starvation for Hondurans, worsening the already existing problems related to disease.[60] Despite the damage, the hurricane helped some rural populations because it forced a change in how the groups used their land. A study in 2002 found that the damaged forests allowed for more agriculture space.[29]

See also

Deadly hurricanes

- List of deadliest Atlantic hurricanes

- Great Hurricane of 1780 – The deadliest Atlantic hurricane on record

- 1900 Galveston hurricane – The deadliest hurricane ever to strike the U.S.

- Hurricane Flora (1963) - Category 4 hurricane which was the fifth-deadliest Atlantic Hurricane on record.

- Hurricane Fifi–Orlene (1974) - Category 2 hurricane which was the third-deadliest Atlantic hurricane on record.

- Typhoon Nina (1975) - Category 4 super typhoon which was the deadliest typhoon on record, and the third-deadliest tropical cyclone worldwide.

- 1970 Bhola cyclone – The deadliest tropical cyclone on record, worldwide

- Storm Daniel (2023) – a medicane which caused catastrophic dam failures that led to thousands of deaths in Libya.

Storms similar in track and/or intensity

- List of Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes

- List of wettest tropical cyclones

- Hurricane Felix (2007) – A Category 5 hurricane that devastated Central America

- Hurricane Eta (2020) – A Category 4 hurricane that also devastated Central America and took a similar erratic track through the Caribbean Sea

- Hurricane Iota (2020) – A Category 4 hurricane that also brought devastating damage to Central America

References

Notes

- ^ All damage totals are in 1998 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

Cited sources

- ^ Viets, Patricia (17 August 2001). "NOAA delivers life-saving disaster-preparedness infrastructure and systems to Central America". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 10 July 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names". NOAA. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. 11 May 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Landsea, Chris (April 2022). "The revised Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT2) - Chris Landsea – April 2022" (PDF). Hurricane Research Division – NOAA/AOML. Miami: Hurricane Research Division – via Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Guiney, John L.; Miles B. Lawrence (28 January 1999). Hurricane Mitch Preliminary Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Lawrence, Miles (24 October 1998). Hurricane Mitch Discussion Number 11 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 31 October 2008. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Avila, Lixion (24 October 1998). Hurricane Mitch Discussion Number 12 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 31 October 2008. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Rappaport, Ed (24 October 1998). Hurricane Mitch Discussion Number 10 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 31 October 2008. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Rappaport, Ed (28 October 1998). Hurricane Mitch Discussion Number 29 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 31 October 2008. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Lawrence, Miles (30 October 1998). Tropical Storm Mitch Discussion Number 36 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 31 October 2008. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Richard Pasch (26 October 1998). Hurricane Mitch Discussion Number 18 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ Richard Pasch; Max Mayfield (26 October 1998). Hurricane Mitch Intermediate Advisory Number 18A (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ Miles Lawrence (26 October 1998). Hurricane Mitch Discussion Number 21 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ a b c "Hurricane Mitch could spare Honduras and slam into Yucatán". ReliefWeb. Agence France-Presse. 27 October 1998. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (14 April 1999). Honduras: Assessment of the Damage Caused by Hurricane Mitch, 1998 (PDF) (Report). United Nations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Central America After Hurricane Mitch: The Challenge of Turning a Disaster into an Opportunity (Report). Inter-American Development Bank. 2000. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Description of the Damage (PDF). Honduras: Assessment of the damage caused by hurricane Mitch, 1998. Implications for economic and social development and for the environment (Report). Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. April 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak Mitch: The Deadliest Atlantic Hurricane Since 1780 (Report). National Climatic Data Center. 23 January 2009. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ Ulate, Juan Carlos (29 October 1998). "Hurricane Mitch at standstill, pounding Honduras". ReliefWeb. Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. "EM-DAT: The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database". Université catholique de Louvain. Archived from the original on 15 February 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d Inter-American Development Bank. "Central America After Hurricane Mitch- Costa Rica". Archived from the original on 19 December 2005. Retrieved 28 April 2006.

- ^ a b c d Inter-American Development Bank (2004). "Central America After Hurricane Mitch- El Salvador". Archived from the original on 26 October 2005. Retrieved 25 April 2006.

- ^ a b c Inter-American Development Bank (2004). "Central America After Hurricane Mitch- Guatemala". Archived from the original on 19 December 2005. Retrieved 25 April 2006.

- ^ "British Aid For Hurricane Victims". BBC News. 4 November 1998. Archived from the original on 1 October 2005. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ^ Inter-American Development Bank (1998). "Central America after HurricaneMitch- Honduras". Archived from the original on 19 December 2005. Retrieved 28 April 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g Edwin L. Harp; Mario Castañeda; Matthew D. Held (2002). Landslides Triggered By Hurricane Mitch In Tegucigalpa, Honduras (PDF) (Report). United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2006. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ United States Geological Study (2002). "Hurricane Mitch:Peak discharge for selected rivers in Honduras" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2006.

- ^ a b c d Philippe Hensel; C. Edward Proffitt (7 October 2002). Hurricane Mitch: Acute Impacts on Mangrove Forest Structure and an Evaluation of Recovery Trajectories (PDF) (Report). United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ Mitch: The Deadliest Atlantic Hurricane Since 1780 (Report). National Climatic Data Center. 23 January 2009. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ a b McSweeney, Kendra; Coomes, Oliver T.; Bebbington, Anthony J. (2011). "Climate-related disaster opens a window of opportunity for rural poor in northeastern Honduras". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (13): 5203–5208. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.5203M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1014123108. ISSN 0027-8424. JSTOR 41125677. PMC 3069189. PMID 21402909.

- ^ a b c Thomas W. Doyle; Thomas C. Michot; Fred Roetker; Jason Sullivan; Marcus Melder; Benjamin Handley; Jeff Balmat (2003). Hurricane Mitch: Landscape Analysis of Damaged Forest Resources of the Bay Islands and Caribbean Coast of Honduras (PDF) (Report). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ a b ERRI Watch Center. "Real-Time Reports Concerning the Devastation Caused by Hurricane Mitch". Archived from the original on 22 April 2006. Retrieved 28 April 2006.

- ^ Thomas W. Doyle; Thomas C. Michot; Fred Roetker; Jason Sullivan; Marcus Melder; Benjamin Handley; Jeff Balmat (2002). "Hurricane Mitch: Landscape Analysis of Damaged Forest Resources of the Bay Islands and the Caribbean Coast of Honduras" (PDF). United States Geological Study. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ a b Inter-American Development Bank. "Central America After Hurricane Mitch-Nicaragua". Archived from the original on 15 December 2005. Retrieved 28 April 2006.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (21 January 2010). "Hurricane Mitch, Central America". Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ Alexa Smith (23 November 1998). "Call-In Day Set to Push For Landmine Ban". World Faith News. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- ^ "Report from Panama". Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2006.

- ^ a b c d e "Mitch: A path of destruction". BBC. 3 December 1998. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2006.

- ^ "Unofficial Reports from Belize". Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2006.

- ^ Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (1998). "Huracán "MITCH" del Océano Atlántico" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- ^ David Roth (2006). "Hurricane Mitch Rainfall Data". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2006.

- ^ Cynthia Corzo, Curtis Morgan and John Barry Herald Staff Writers. "The Loss of the Windjammer, Fantome". Archived from the original on 26 October 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2006.

- ^ Angus MacSwan (27 October 1998). "Ferocious Hurricane Mitch threatens Central America". ReliefWeb. Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- ^ "Unofficial Reports from Jamaica". Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2006.

- ^ "Unofficial Reports from the Cayman IslandsJamaica". 1998. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2006.

- ^ Jay Barnes (2007). Florida's Hurricane History. 0807830682. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-8078-2443-6.

- ^ Lynne Kelleher (10 November 1998). "Hurricane Mitch leaves 30,000 homes in dark out after night of chaos". The Mirror. London. Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ "Worldwide Tropical Cyclone Names". National Hurricane Center. 4 March 2003. Archived from the original on 11 April 2003. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ Inter-American Development Bank (2004). "Central America After Hurricane Mitch". Archived from the original on 19 December 2005. Retrieved 25 April 2006.

- ^ Allen Clinton, CARE Press Officer. "Remembering Hurricane Mitch for Better and for Worse". Archived from the original on 15 November 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2006.

- ^ Pan-American Health Organization. "Disease Threat following Hurricane Mitch". Archived from the original on 26 June 2006. Retrieved 30 April 2006.

- ^ United States Geological Survey. "Coral Reefs in Honduras: Status after Hurricane Mitch". Archived from the original on 17 April 2006. Retrieved 30 April 2006.

- ^ a b c d General Trends 1999–2000 (PDF) (Report). Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. 2000. Retrieved 8 June 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c General Trends 1998–1999 (PDF) (Report). Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. 1999. Retrieved 8 June 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ General Trends 2001–2002 (PDF) (Report). Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. 2002. Retrieved 8 June 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Mariela Naranjo; et al. (Summer 2008). "Study of a Leptospirosis Outbreak in Honduras Following Hurricane Mitch and Prophylactic Protection of the vax-SPIRAL® Vaccine" (PDF). MEDICC Review. 10 (3).

- ^ General Trends 2002–2003 (PDF) (Report). Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. 2003. Retrieved 8 June 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Hurricane Mitch | storm, Central America [1998]". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ Symanski, Richard (1998). "Honduras: When the Saints Arrive". Geographical Review. 88 (4): 571–579. doi:10.2307/215713. ISSN 0016-7428. JSTOR 215713.

- ^ "Honduras: About Honduras". St. Basil the Great Catholic Church. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "Environmental Impacts of Hurricane Mitch". Environmental Health Perspectives. 107 (3): A139 – A140. 1999. doi:10.2307/3434497. ISSN 0091-6765. JSTOR 3434497. PMC 1566390. PMID 10391735.

External links

![]() Media related to Hurricane Mitch at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hurricane Mitch at Wikimedia Commons

- Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes

- Hurricanes in Florida

- Hurricanes in El Salvador

- Hurricanes in Guatemala

- Hurricanes in Honduras

- Hurricanes in Nicaragua

- Atlantic hurricanes in Mexico

- Retired Atlantic hurricanes

- Hurricanes in Europe

- 1998 Atlantic hurricane season

- 1998 natural disasters

- 1998 in Mexico

- 1998 in Florida

- 1998 in El Salvador

- 1998 in Guatemala

- October 1998 in North America

- November 1998 in North America

- Hurricanes in Costa Rica

- Hurricanes in Panama